Features

Bodies from the Library: A Q&A with the editor

We interviewed Tony Medawar about his collection Bodies from the Library in 2018. Recently, we got back in touch to discuss the brand new collection Bodies from the Library 2: Forgotten Stories of Mystery and Suspense by the Queens of Crime and other Masters of Golden Age Detection.

Can you tell us a bit about how Bodies from the Library (Volume 2) came about?

The idea for an annual anthology of unpublished, rare and forgotten stories came from my publisher, the legendary David Brawn. The hard part of course is unearthing unknown stories but that has been my hobby for nearly 40 years so I have amassed quite a store. And I have been lucky in that others, including the book dealer Jamie Sturgeon and the Golden Age authorities Curtis Evans, Stephen Leadbeatter and Arthur Vidro, as well as other enthusiasts like me, have pointed me in the direction of lost gems.

How did you come across the Christie stories featured in these collections?

The story included in Volume 2 of Bodies from the Library, 'The Man Who Knew', was first published in one of John Curran’s two volumes entitled Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks. However, the story had never been included in any collection of her work. As regards to the Christie story I included in Volume 1 of Bodies from the Library, ‘The Wife of the Kenite’, I knew that a story of that title existed because I had seen it in an Italian magazine and I had translated it myself, (badly, I might add). When I came across a reference in an obscure Australian newspaper to a story called ‘The Wife of the Kenite’, I knew immediately what it must be - the original version of the story, in English; happily, it was easy enough to follow up that small clue and locate a copy of the magazine where the story appeared. I wanted to include the story in Bodies from the Library because it is so unusual and because it is an early example of a situation to which she would return in at least two more short stories, a radio play and a novel.

The book also contains two unpublished novellas from Edmund Crispin and Dorothy L. Sayers. It is like you are a detective in your own right! How do you find these works?

I located both stories - and some similar treasures by other authors, which incidentally are scheduled to appear in the third and fourth volumes, by going through the authors’ archives held, respectively, in the UK and in the US. I cannot begin to describe the excitement of discovering an unpublished and completely unknown novella featuring the great detective Gervase Fen as well as an unpublished long Lord Peter Wimsey short story by Dorothy L. Sayers. I know from the reader feedback I have received that these stories will be, for many, the highlight of the collection. Unearthing the unknown, finding the forgotten and locating the lost does take some detection skills but even more important are luck and perseverance - there are a lot of newspapers and periodicals to go through and this takes time, especially as several of the the purportedly complete online archives are in fact incomplete.

There are so many types of detective across the collection. From deceptive mediums to listening servants, conventional police officers to more varied ‘crack teams’. Can you talk a little about the types of detectives we see in this collection?

One of the great joys of crime and detective fiction is the sheer variety of detectives: detectives with a special skill like the blind sleuth Max Carrados who was created by Ernest Bramah and appeared in the first volume of Bodies from the Library; detectives with an unusual job or without any job at all - aristocratic amateurs like Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion and Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey whose final case, ‘The Locked Room’, was published for the first time anywhere in Volume 2 of Bodies from the Library. And as there is variety among detectives there is huge variety in the setting of crime and mystery stories of the Golden Age – in the two volumes of Bodies from the Library there are stories set in tower blocks and manor houses as well as the heat of South Africa and Victorian London. Volume 3 of Bodies from the Library will feature a previously unpublished story set in an art gallery, featuring one of the most famous sleuths of the Golden Age.

Do you have a favourite story amongst this anthology?

My favourite story in the second volume of Bodies from the Library is not, surprisingly, by Agatha Christie but by her great friend and fellow member of the Detection Club, Margery Allingham. It is a radio play called ‘Room to Let’ and in it Allingham not only provides an explanation of the infamous ‘Jack the Ripper’ Murders in Victorian London but also gives us an ingenious locked room puzzle. And all in half an hour.

A bit about Tony Medawar

Editor Tony Medawar is a detective fiction expert and researcher with a penchant for tracking down rare stories. His most recent publications are Murder She Said: The Quotable Miss Marple and Bodies from the Library (Volume 2), and he has also edited a number of collections of previously uncollected stories including While the Light Lasts (Agatha Christie), The Avenging Chance (Anthony Berkeley), The Spotted Cat (Christianna Brand), A Spot of Folly (Ruth Rendell), and the forthcoming The 9.50 Up Express and Other Mysteries from Inspector French’s Casebook (Freeman Wills Crofts) and The Island of Coffin and Other Mysteries from Dr Fabian’s Casebook by John Dickson Carr. For more information about the Golden Age of Detective Fiction and the conferences that inspired the annual Bodies from the Library anthologies, visit: bodiesfromthelibrary.com.

August 2018: Our Original Q&A with the Editor

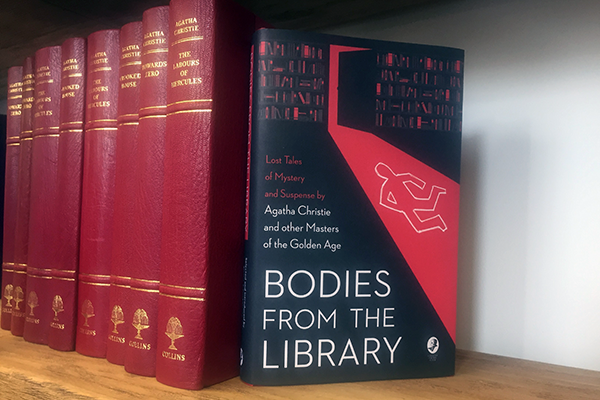

Bodies from the Library brings together 16 forgotten tales that have either been published only once before – perhaps in a newspaper or rare magazine – or have never before appeared in print. 'The Wife of the Kenite' was likely written in South Africa in 1922 when Christie was accompanying her first husband Archie on a trip. It was previously published just once, in Australia’s Home Magazine in September 1922. We asked the editor, Tony Medawar, a few questions about the collection, and Christie’s lesser known story.

What draws you to work from the Golden Age?

For me, as someone who grew up in London during the depression of the 1970s, the mysteries of the Golden Age provided a place of refuge from strikes and shortages – I can distinctly remember reading And Then There Were None under my bedcover during a scheduled power cut! Entertaining puzzles, generally well-written, often with unusual settings and almost always with engaging characters. Though my parents admired Chandler and Hammett, the clichés of the so-called hard-boiled fiction of the American Golden Age were never as appealing and, for all their professed realism, the plots and personalities seemed even more improbable and unrealistic than those presented by Agatha Christie and her contemporaries. And the stories I read when I was young have stuck with me. While I read and review a lot of contemporary fiction, including crime fiction and writers that hark back to the best of the Golden Age – like Ann Cleeves, Elly Griffiths and Christopher Fowler – I often find myself drawn back to the bodies in the library, bones in the brickfield, or to crimes on the footplate ... To someone who has read little crime fiction, the notion of re-reading a murder mystery might be baffling but to me, and many millions like me, it is like meeting old friends once more, travelling on the shoulder of one of my favourite detectives and watching admiringly as he or she unravels the clues that have been so carefully laid out by the author. It was with the aim of finding lost stories featuring my favourite characters that I first began searching for clues to the location of ‘lost’ works in the files of literary agents and in newspaper and magazine archives like the British Library. And I have had no end of pleasure in being able to add forgotten cases to the chronologies of some of the best-known detectives in Golden Age fiction.

What intrigues you about Agatha Christie’s works that are set in a foreign land?

Agatha Christie is often described by people who haven’t really read her as a “cosy” writer, imagining her works are confined to village settings, but this just isn’t true. Christie was extremely well-travelled and made excellent use of the places she visited. She set crimes all over the world, including in Paris and Baghdad, and of course she staged her murders everywhere – from Murder in Mesopotamia, to isolated islands, and even to ancient Egypt. And in all of her stories, the location is beautifully realised – like the tropical island setting of A Caribbean Mystery or the South African veldt in The Wife of the Kenite, the intriguing story included in this collection, Bodies from the Library.

We loved the sense of foreboding in 'The Wife of Kenite'. What other themes are covered in Bodies from the Library?

The stories in Bodies from the Library are all very different and, unusually, the collection does not have a common theme other than the fact that the stories are all obscure and hard to find. For me, Agatha Christie’s story stands out because it is so unusual and quite atypical of her work, something in fact closer to horror and some of the stories in The Hound of Death than to the more straightforward detective stories for which, of course, she is best known. A second volume of Bodies from the Library will be published next year and I hope its contents, which we have just finalised, will surprise and delight readers of Golden Age fiction too.

How do Golden Age authors vary in their coverage of war and revenge?

One criticism levelled at writers of Golden Age fiction is that they did not illumine our understanding of the Second World War and sometimes wrote as if it was not happening. While many writers, including Christie, did incorporate both World Wars into their plots – Taken at the Flood or N Or M? for example - there is some truth in this generalisation. However, surely one of the reasons that crime fiction became so popular in the late nineteenth century – and remained so through two world wars and up to the present day – is that it provides respite from the quotidian horrors of real life reported all too vividly by the press, and on television. And revenge is a staple of crime fiction, fuelling many of the best-remembered cases of Mr Sherlock Holmes, and is still a favourite motive today.

Agatha Christie said ‘When once you adopt crime, it’s difficult to give it up, I know I can never do so.’ Would you say the same about crime readers?

Crime fiction is certainly addictive and that is why one of the great pleasures in life for me is finding someone who is genuinely able to recreate the style and characters of one of my favourite authors successfully – such as Stella Duffy’s Inspector Alleyn novel, Money in the Morgue, or Mike Ripley’s Mr Campion mysteries – or tracking down forgotten works by a favourite author. I have been lucky enough to locate many uncollected and unpublished stories and plays by Agatha Christie and her contemporaries and I can assure you that the thrill of finding something new is completely exhilarating. I hope many readers will experience something similar when they read 'The Wife of the Kenite'.

In your opinion, which other works by Christie explore similar themes to The Wife of Kenite?

I am keen for fans to find this out when they read it. Agatha Christie was ingenious in the way she re-used themes and plots, and in how she developed ideas used in short stories and radio plays into novels, sometimes in a way that is not immediately obvious – the similarities between The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and Hercule Poirot’s Christmas for example, or between Death on the Nile and They Do It with Mirrors. One could write a book about it. And fortunately someone has, John Curran, the Christie expert whose two studies of Christie’s approach to her work - Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks and Agatha Christie’s Murders in the Making - are absolutely essential reading.

Bodies from the Library and Bodies from the Library 2 are now available in the UK and the USA.

USA

USA