Features

Agatha Christie's Witches

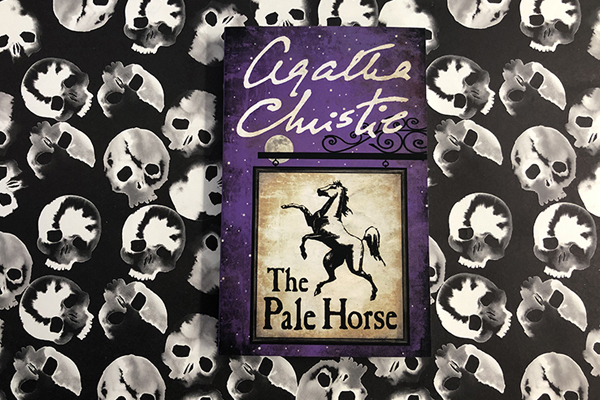

The release of The Last Séance: Tales of the Supernatural, as well as the recent TV production of The Pale Horse, reminds us once again how unconventional Christie can be as a mystery writer. Her inclusion of witches is just one of the fascinating, spookier elements of her writing. We caught up with Agatha Christie expert Chris Chan, to find out more about her witches.

Early in The Pale Horse, Mark Easterbrook and Hermia discuss a production of Macbeth they’d just seen at the Old Vic. Though many aspects of the show receive praise, Hermia declares that the presentation of the three witches were “Awful!... They always are.” David, a theatre aficionado, declares that if he were given the chance to direct a production of Macbeth, he would ““make them very ordinary. Just sly quiet old women.”

The characters further discuss David’s directing ideas, saying:

“I don’t see how you could produce the witches as ordinary old women,” … “They must have a supernatural atmosphere about them, surely.”

“Oh, but just think,” said David. “It’s rather like madness. If you have someone who raves and staggers about with straws in their hair and looks mad, it’s not frightening at all!...”

“So your idea of the witches,” I said, “is three old Scottish crones with second sight—who practise their arts in secret, muttering their spells around a cauldron, conjuring up spirits, but remaining themselves just an ordinary trio of old women. Yes—it could be impressive.”

In that very book, the characters come across a trio of self-professed witches. Mark meets the coven, Thyrza Grey, Sybil Stamfordis, and Bella Webb, who profess a mastery of the Dark Arts, mediumistic powers, and other magical abilities. These witches are not over-the-top cackling exemplars of wickedness, but they are unsettling, confident in their abilities, and seemingly devoid of regret. Thryza seems to radiate power and often seems able to read minds; Sybil covers herself with saris, costume jewellery, and an overall atmosphere of unearthliness; and Bella, by Thryza’s own declaration, is a “disconcerting” woman. What they really believe is up for debate, but part of the mystery of The Pale Horse comes from determining whether or not the alleged witches have magical powers or not.

Christie repeats the aforementioned sentiments in Nemesis. There, Miss Marple recalls the time when her nephew Raymond took her to see a production of Macbeth. “You know, Raymond, my dear, if I were ever producing this splendid play I would make the three witches quite different. I would have them three ordinary, normal old women. Old Scottish women. They wouldn’t dance or caper. They would look at each other rather slyly and you would feel a sort of menace just behind the ordinariness of them.” Miss Marple has these recollections while staying with a trio of elderly sisters, and the sleuth isn’t quite sure why the Bradbury-Scott sisters remind her so much of the Macbeth witches. Lavinia, Clotilde, and Anthea seem like pleasant, kind women, but one seems to be highly strung, another’s still waters run deep, and another hides a dark secret. They seem so nice, and yet… in classic Christie fashion, they’re all potential killers, and the truest embodiment of what Christie twice described as the ideal Macbeth witches.

While these are the most prominent examples of witches in Christie’s works, there are many other examples. Endless Night features Esther Lee, a self-described gypsy, who curses the young couple who move onto the land dubbed Gipsy’s Acre. Esther Lee’s character and the plot have their origins in the Miss Marple short story 'The Case of the Caretaker'. Christie got the idea for the narrative from her grandson’s other grandmother, who received the dedication “To Nora Prichard from whom I first heard the legend of Gipsy’s Acre.” Nora explained a Welsh tale of curses and danger to Christie, who adapted them into her own sort of dark tale.

There are many other minor witches, warlocks, and other characters with alleged magical powers in Christie stories. A minor subplot in Murder is Easy focuses on some practitioners of the dark arts who unsettle the village with their rituals. The head of the coven is Mr. Ellsworthy, an antique shop owner whose hands are unusually long, pale, and occasionally spattered with blood.

A psychic in ‘The Blue Geranium’ foresees doom, and when her predictions result in death, a household wonders just what powers she possesses. Other examples of women who profess supernatural abilities in the Miss Marple short story collection The Thirteen Problems are a woman who claims to have received the powers of the Goddess of the Moon in ‘The Idol House of Astarte’, and a spiritualist who convinces a wealthy old man to leave her his vast fortune in ‘Motive vs. Opportunity’.

Teenage girls dabble in deadly curses in Evil Under the Sun and Spider’s Web, and a séance brings an unexpected message of murder in The Sittaford Mystery. Isabel and Julia Tripp are a pair of sisters who believe they can contact the spirit world in Dumb Witness. More threatening is Dr. Andersen, the leader of a cult, ‘The Flock of the Shepherd’, who professes incredible spiritual powers he can share with his followers. A pattern soon emerges – Andersen converts wealthy people, who suddenly die of seemingly natural causes.

Ancient Egyptian curses play a role in ‘The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb,’ where members of an archaeology expedition drop dead one by one, and the members of an ancient Egyptian family in Death Comes as the End wonder if a supernatural force, possibly the curse of a ghost, is causing a family annihilation.

On a lighter note, in ITV's Agatha Christie’s Poirot TV series, Miss Lemon had a recurring interest in the occult. In the novel Peril at End House, Poirot presses Hastings to fake mediumistic powers to help catch a killer. A woman with admittedly no psychic powers takes on the role of fortune teller at a fête in Dead Man’s Folly. Mrs. Goodbody, a local “witch” in Hallowe’en Party, tells fortunes and shows teenage girls their future husbands with the help of some clever stagecraft, special effects, and acting skills. Mrs. Goodbody’s “powers” are used all in good fun and entertain the children… until one girl is drowned in the apple-bobbing vat.

Plenty of Christie’s mysteries allude to the supernatural and to witches, and within these she frequently manages to create auras of genuine power and menace.

Written by Agatha Christie expert, Chris Chan

So with all this talk of witches, you might wonder if Christie took after fellow author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a devoted spiritualist. We asked Chris about Agatha Christie's views of the supernatural. He had this to say:

"In An Autobiography, there's a brief passage in the chapter ‘Flirting, Courting, Banns Up, Marriage’ where she discusses her relationship with a man named Wilfred and how he got her to read a lot on spiritualism and theosophy:

“So life went placidly on. Every two or three weeks Wilfred came for the weekend. He had a car and used to drive me around. He had a dog, and we both loved the dog. He became interested in spiritualism, therefore I became interested in spiritualism. So far all was well. But now Wilfred began to produce books that he was eager for me to read and pronounce on. They were very large books–theosophical mostly. The illusion that you enjoyed “whatever your man enjoyed didn’t work; naturally it didn’t work–I wasn’t really in love with him. I found the books on theosophy tedious; not only tedious, I thought they were completely false; worse still, I thought a great many of them were nonsense! I also got rather tired of Wilfred’s descriptions of the mediums he knew. There were two girls in Portsmouth, and the things those girls saw you wouldn’t believe. They could hardly ever go into a house without gasping, stretching, clutching their hearts and being upset because there was a terrible spirit standing behind one of the company. ‘The other day,’ said Wilfred, ‘Mary–she’s the elder of the two–she went into a house and up to the bathroom to wash her hands, and do you know she couldn’t walk over the threshold? No, she absolutely couldn’t. There were two figures there–one was holding a razor to the throat of the other. Would you believe it?” “I nearly said, ‘No, I wouldn’t,’ but controlled myself in time. ‘That’s very interesting,’ I said. ‘Had anyone ever held a razor to the throat of somebody there?’

‘They must have,’ said Wilfred. ‘The house had been let to several people before, so an incident of that kind must have occurred. Don’t you think so? Well, you can see it for yourself, can’t you?’

But I didn’t see it for myself. I was always of an agreeable nature however, and so I said cheerfully, of course, it certainly must have been so.

Then one day Wilfred rang up from Portsmouth and said a wonderful chance had come his way. There was a party being assembled to look for treasure trove in South America. Some leave was due to him and he would be able to go off on this expedition. Would I think it terrible of him if he went? It was the sort of exciting chance that might never happen again. The mediums, I gathered, had expressed approval. They had said that undoubtedly he would come back having discovered a city that had not been known since the time of the Incas. Of course, one couldn’t take that as proof or anything, but it was very extraordinary, wasn’t it? Did I think it awful of him, when he could have spent a good part of his leave with me?

I found myself having not the slightest hesitation. I behaved with splendid unselfishness. I said to him I thought it a wonderful opportunity, that of course he must go, and that I hoped with all my heart that he would find the Incas’ treasures. Wilfred said I was wonderful; absolutely wonderful; not a girl in a thousand would behave like that. He rang off, sent me a loving letter, and departed.

But I was not a girl in a thousand; I was just a girl who had found out the truth about herself and was rather ashamed about it. I woke up the day after he had actually sailed with the feeling that an enormous load had slipped off my mind. I was delighted for Wilfred to go treasure-hunting, because I loved him like a brother and I wanted him to do what he wanted to do. I thought the treasure-hunting idea was rather silly, and almost certain to be bogus. That again was because I was not in love with him. If I had been, I would have been able to see it through his eyes. Thirdly, oh joy, oh joy! I would not have to read any more theosophy.”

So Christie was exposed to a lot of mediums and spiritualism and theosophy, but after all of the pressure put on her by Wilfred, she was thoroughly turned off by the whole experience. She included her knowledge of that sort of thing for colour and atmosphere in her books to great effect, but she didn't believe in it herself."

USA

USA